News Highlight

Constitution Bench to take up Section 6A of the Citizenship Act for preliminary determination.

Key Takeaway

- A Constitution Bench led by the Chief Justice of India on January 10 said it would first take up for preliminary determination whether Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955 suffers from any “constitutional infirmity”.

- Section 6A was a special provision inserted into the 1955 Act in furtherance of a Memorandum of Settlement.

- And it was called the ‘Assam Accord’ and signed on August 15, 1985, by the Rajiv Gandhi government.

- The Accord came at the end of a six-year-long agitation by the All Assam Students Union (AASU).

- It is to identify and deport illegal immigrants from the State, mostly from neighbouring Bangladesh.

Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955

- Background

- Section 6A of the Citizenship Act of 1955 provides provisions about the citizenship of those covered by the Assam Accord (1985).

- This clause was added to the Citizenship Act of 1955 in 1985 due to an amendment.

- Section 6A of the act states that everyone who migrated to Assam on or after January 1, 1966, but before March 25, 1971, from the specified territory is subject to the act.

- Since they are Assamese residents, they must register for citizenship under Section 18.

- As a result, this act establishes March 25, 1971, as the deadline for awarding citizenship to Bangladeshi migrants in Assam.

Assam Accord

- About

- Between 1979 and 1985, Assam saw massive political instability, the breakdown of the state government, the president’s rule, and tremendous ethnic bloodshed.

- The government’s elections were boycotted, and violence based on linguistic and tribal identities killed thousands throughout the state.

- Finally, to deal with the issue, the then-Rajiv Gandhi government signed the Assam Accord on 15 August 1985, a Memorandum of Settlement (MoS) with the agitation leaders.

- As per this accord:

- Foreigners who arrived in Assam between 1951 and 1961 were to be granted full citizenship, including the opportunity to vote.

- Furthermore, migrants who arrived after 1971 were to be deported.

- Those who immigrated between 1961 and 1971 would be denied voting privileges for ten years but would have full citizenship rights.

What is the current issue?

- Several petitions in the Supreme Court have been brought in recent years challenging the constitutionality of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act.

- This is because the new central government rule contradicts Article 6 of the Constitution.

- Furthermore, it states that the cut-off date for determining citizenship in India is July 19, 1948.

- Several Assamese organisations, including Assam Sanmilita Mahasangha, Assam Sahitya Sabha, Assam Public Works, and All Assam Ahom, have challenged Section 6A of the Act in court, claiming that the section discriminates against migrants in the country.

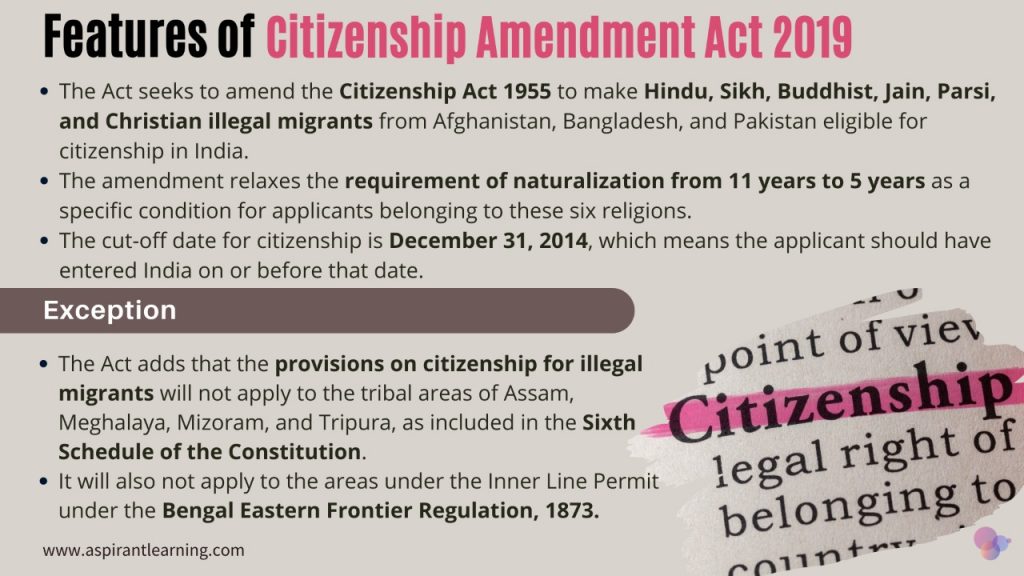

Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019

- About

- Firstly, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 seeks to amend the Citizenship Act of 1955.

- Additionally, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 (CAA) was notified in 2019 and came into force in 2020.

- Objectives

- Firstly, the CAA aims to grant Indian citizenship to persecuted minorities.

- They include Hindu, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, Parsi and Christian from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

- Those from these communities who had come to India on December 31, 2014, faced religious persecution in their respective countries.

- Furthermore, they will not be treated as illegal immigrants but given Indian citizenship.

- Exceptions

- The Act does not apply to tribal areas of Tripura, Mizoram, Assam and Meghalaya because of being included in the 6th Schedule of the Constitution.

- It also does not apply to the areas under the Inner Limit notified under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873, which will also be outside the Act’s purview.

- Reduced period

- It relaxes the period of stay in Inda for being eligible for citizenship by naturalisation from 11 to 5 years.

Conclusion

- Firstly, the parliament has unfractured powers to make laws for the country regarding Citizenship.

- But the opposition and other political parties allege this Act by the Government violates some of the constitution’s essential features, like secularism and equality.

- In addition, it may reach the doors of the Supreme Court, where the Supreme Court will be the final interpreter.

- If it violates the constitutional features and goes ultra-wires, it will be struck down; if it is not, we will continue to have the law.

Pic Courtesy: Business Standard

Content Source: The Hindu